Coaching tends to be a popular form of development for customer service representatives. The general methods of formal coaching and mentoring involve:

si ing alongside the agent listening to calls;

one-to-ones;

listening remotely or to recordings and providing feedback;

coach and agent jointly listening to recordings;

mentoring – a more experienced agent giving feedback;

a roving coach providing ad hoc feedback;

coach and team members all listening to recordings;

buddying;

peer coaching;

informal coaching;

self-coaching.

Sitting alongside the adviser

‘Sitting by Nellie’ is a term o en associated with coaching and teaching someone how to do a job. It enables the coach and the learner to observe each other and to listen in to calls. In other industries there is a requirement for physical proximity because of the need to observe performance; however, in contact centres, information and communications technology allows remote listening and feedback.

One-to-one coaching

Not all coaching should be provided in public spaces such as at the workstation. There are many circumstances where it is advisable to conduct the coaching session in private. The presence of other people can inhibit both the coach and the learner and prevent true rapport from being developed. There should be a dedicated coaching room(s) with the necessary equipment, furnished to make it a relaxed environment.

Listening to recordings helps to highlight things that may not be noticed:

A lot of the time it isn’t what they say, it’s the tone in which they say it. . . I play something and I’ll just stop it and say, ‘Shall we listen to that again?’, rewind it and then they’ll go, ‘I didn’t know I said it like that’. It makes them analyse themselves and really wake up to their mistakes.’ (Taylor, 1998: 93).

Listening remotely

Listening remotely to a call can be done with or without the knowledge of the adviser and its use will o en depend on work practices and culture. Some advisers will not be unduly concerned that someone is listening in to their calls while others may become so anxious that it may affect their performance.

Where this form of surveillance is used without informing the adviser it is hard not to consider it a ‘Big Brother’ tactic. If the purpose is to continually keep advisers ‘on their toes’, this suggests that the organization does not fully trust the advisers to produce a professional performance.

Where remote listening is carried out with the knowledge of the adviser it can be a very helpful means of coaching and encouraging performance. It is not intrusive to the customer and provides the opportunity for rapid feedback and guidance as soon as the call is completed.

Mentoring

Mentoring is o en undertaken between a more experienced senior person and one with fewer skills and experience. In many organizations the two people o en work in different departments and do not have direct daily interaction. In this way, the relationship can be more open and supportive than if one had direct operational responsibility for the other.

The roaming coach

Many coaches spend some of their time walking the floor and providing support at the advisers’ desks and this can be systematically timetabled as well as being impromptu. The benefit of the latter is that coaching and feedback can be directly related to a particular need, eg after a challenging call. Also, the potential for learning is high if it is close in time to a specific issue. Coaches ‘walking the floor’ also give advisers the opportunity to seek more informal assistance than arranging a formal coaching session.

Coach and team members listen to recordings

Coaching need not be purely one-to-one. Weekly team meetings provide good opportunities to listen to recordings as a group, with colleagues giving advice and recommendations about how to address specific issues, eg a difficult caller or problem. On the whole, it is better to choose incidents that have relevance to the whole team rather than one person.

Buddying

Buddying is a popular and widely used form of coaching, with 75 per cent of centres using this method (Dimension Data, 2005: 209). It is also particularly successful with new employees who are sometimes paired with experienced advisers for the first six months of employment to provide advice and support. To increase motivation, incentive payments have been made to mentors if the new recruit remains with the organization for a minimum period of time (Income Data Services, 2004).

Informal coaching

Coaching can also occur informally and in many contact centres the CSRs sit in close proximity. This is o en in the form of pods, which consist of about eight to 10 people working in a circle facing one another. This physical structure enables less experienced operators to temporarily interrupt the call and seek advice and information from their colleagues.

Coaching oneself

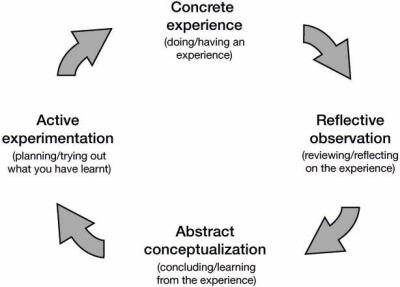

Self-monitoring during a call is a skill used by all experienced advisers as a means of assessing how well they are conducting the conversation with the caller. Advisers can also reflect on a call after it has happened and mentally replay language, tone and fluency to identify what went well and what could have gone be er.

Recorded conversations can also be used by advisers to monitor, assess and develop themselves through listening again to calls and assessing their own performance figures. Visual computer analysis of calls can also be used to highlight where the adviser interrupts, speaks over the caller, etc.

The benefits of self-coaching are that it is less threatening and allows the learners to self-monitor, which will develop a continuous reflection of their behaviour. If this is carried out successfully it reduces the load on the team leader.

Making available call performance recordings and data to the adviser may at first appear threatening; however, if it is done in a spirit of learning and trust then this can be a very successful way of encouraging development.